The messages from the Dace and the Darter, warning of the advance of Kurita’s fleet, began arriving in Flag Plot aboard USS New Jersey at 6:20 am on Oct. 23. Halsey and his staff pondered the significance of the sightings by the two submarines.

Halsey was not the only fleet commander tracking the Japanese movements. The Seventh Fleet – “MacArthur’s Navy” – of old battleships and small “jeep” carriers floated off the invasion beach, supporting the landings with gunfire and strafing and bombing runs. Aboard his flagship at anchor in Leyte Gulf, Adm. Thomas Kinkaid, the commander of the Seventh Fleet, weighed in with his prediction. In a message to all commanders (MacArthur, King, Nimitz and Halsey) sent shortly after 10:00 am, Kinkaid suggested that the Japanese warships were headed to the Philippines to stage what Kinkaid called a “magnified Tokyo Express.” Kinkaid suggested that by sea, under cover of night, the Japanese were planning to run reinforcements to their troops battling the invading American forces at Leyte.

To counter the Japanese, Nimitz directed all Pacific Fleet units to cover and support forces of the southwest Pacific in the seizures of Leyte. The 3rd Fleet was directed “to destroy enemy naval and air forces in or threatening the Philippine area”. Halsey’s instructions included one sentence that caused considerable controversy later. It read, “In case opportunity for destruction of major portion of the enemy fleet offer or can be created, such destruction becomes the primary task.”

Halsey concluded that the Japanese were running some kind of Tokyo Express but he wondered where were the Japanese carriers. The submarines had spotted battleships but no carriers. Worried about his pilots so exhausted he ordered one of the carrier groups, Adm. John S. McCain’s Task Group 38.1 to continue to Ulithi to resupply and R&R. McCain’s five ships carried roughly 400 or two-fifths, of the Third Fleet’s 1000 warplanes. Halsey felt confident that he had enough to handle a “magnificent Tokyo Express.” He ordered the remaining carrier groups to close on the Philippine shore and prepare for action.

At dawn on Oct. 24, the Third Fleet sent search flights racing to the west, looking for the Japanese ships. At 8:20, came the first report from Lt. Bill Verity, “I see ’em! Big ships!” Two minutes later, Cdr. Mort Eslick gave a count of 25 ships off the southern tip of Mindoro. Halsey took no time in deciding what to do. Officially, Halsey was overall commander of the Third Fleet but “tactical” control of the fast carrier task force belonged to Adm. Marc Mitscher. At 8:37 am. Halsey in his best radio voice commanded: “Strike! Repeat: Strike! Good luck!”

At 8:46 am, Halsey ordered Admiral McCain’s carrier group to reverse course and prepare to refuel at sea. Halsey realized he would need all of his carrier planes. McCain’s force was already 600 miles away. It would take him more than a day to return.

At 8:20, standing on the bridge of the Yamato, Admiral Kurita sighted three American planes to the north. The tension rose on the bridge. After the sinking of the Atago and the Maya the day before, lookouts were on edge and saw periscopes everywhere.

At last, shortly aft 10:30 am, the Americans arrived in full force. Thirty planes (Hellcats, Helldivers and Avengers could be seen breaking tight formation as the bombers commenced their runs. The Americans planes fearlessly bore in, bombing or just flying low and straight on their torpedo runs.

At noon, the Americans came again. Enormous geysers erupted around the Musashi as a pair of torpedoes buried their heads in her bow. Water was now slowly flooding the Musashi’s forward compartments. From the high bridge of the Yamato, Admiral Kurita watched wordlessly as the American planes broke off their attack and disappeared back over the eastern horizon. He knew that more were coming. Admiral Nishimura, scheduled to advance on Leyte through Surigao Strait, was reporting that he, too, was under attack. Kurita had not heard a word from Admiral Ozawa, whose decoy fleet was supposedly luring away Halsey’s carriers somewhere to the north – though not very effectively, judging from the swarms of American carrier planes descending on Kurita’s ships.

Kurita had been radioing Combined Fleet headquarters in Tokyo and First Air Fleet headquarters in Manila since 8:00 am requesting air cover but he had received no response. He decided to send a message to his superiors. It was a request for information in a classically Japanese roundabout way to shame them but he received no answer either.

At 3:10 in the afternoon, a fifth wave of American planes descended on the Japanese fleet. It was the biggest attack yet, about a hundred planes. They circled the Musashi. Bomb hits sprayed shrapnel across the decks, cutting down sailors who wore hachimaki “victory” headbands, patterned after the white clothes that ancient samurai wore around their heads, signifying their expectation of death. (American sailors, by contrast, wore metal helmets.) A bomb tore through the bridge of Musashi, killing most of the officers. Admiral Inoguchi was spared. But shrapnel swept across the observation tower where he was, slicing into his shoulder. The ships was by now, almost helpless, decks awash.

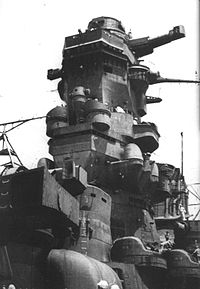

On the afternoon of Oct. 24, Musashi reeled under a crushing nineteen torpedoes and seventeen bomb blasts. When she finally rolled over and sank, Musashi carried more than 1,000 officers and sailors, almost half the Musashi’s crew to their watery graves. In addition to sinking the Musashi and crippling the cruiser Myoko, the day-long attacks had damaged the Yamato and two other battleships.

On the bridge of the Yamato, Kurita’s staff knew the fleet was in trouble. Captain Otani, Kurita’s operations officer, urged his commander to turn the fleet around. He reasoned that before darkness, the Americans could launch another three attacks. Kurita listened impassively and finally nodded his assent.

Still powerful with his galaxy of battleships, cruisers and destroyers, Admiral Kurita temporarily halted his voyage toward Leyte in hopes that forays of land-based aircraft might drive off the American carriers or protect his fleet from the deadly stings of the American planes. Unfortunately, there were no planes available to support Kurita.

To be continued . . .

Note: Researchers led by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, aboard Allen’s motor yacht, the M.Y. Octopus, had located the imperial Japanese Navy battleship, Musashi, at a depth of approximately 3,280 feet (one kilometer) in Philippine waters on March 2, 2015. The 73,000-ton (66,224 metric tons) Musashi and sister ship Yamato were the largest battleships the world has ever known.

Sources:

The Pacific War by William B. Hopkins

Sea of Thunder by Evan Thomas

Reblogged this on Rosalinda R Morgan.

LikeLike

The Musashi and Yamato were magnificent warships. It was actually sad that we needed to destroy them. But we saved many an Allied sailor by doing so.

Great research, Rose, you brought the battle to life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. Yes, Musashi and Yamato were magnificent ships. They called Musashi “The Palace” and Yamato “Hotel Yamato”. The crews of both ships had been told that they were unsinkable. The crews of Musashi were told that “If it sinks, Japan will sink with it. And if Japan falls, we should all go down with it.”

LikeLike

FYI Mort Eslick of VB-18 was actually Mark Eslick, and he was KIA October 12, 1944, almost two weeks before this event took place. Carl Solberg’s account “Decision and Dissent” is wrong on this point, and subsequent authors have likewise got this wrong. Max Adams was the VB-18 pilot on this sector search with his rear-seater Cornelius Clark. Also, Bill Verity doesn’t seem to exist and there is no record of Cabot planes being part of Adm. Bogan’s search groups that morning, so it’s unlikely any fighter from Cabot participated. Instead, Donald Watts of VF-18 was the pilot labeled “5F Intrepid” in the Com 3rd Fleet reports which give the actual number of ships as reported to Halsey that morning. Historians continue to get this wrong but hopefully in the future it will be corrected!

LikeLike

Thanks for your input. I got another book about the Battle of Leyte Gulf and I can’t find any of these names except for Max Adams. I only based my blog’s narrative on what I read. I grew up in the Philippines and hoping by next year will be able to go there and do some research about the Battle of Leyte Gulf. It is one of the turning points of the war and I find it quite interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That will be a great experience! It definitely is an important battle and I hope you’re able to go visit the site. The names/information are derived from the aircraft action reports from USS Intrepid’s Air Group 18, as well as the 3rd Fleet Communications Log which shows the transmissions bouncing around between pilots, carrier task group commanders and Admiral Halsey. I also have a picture of the citation for the Distinguished Flying Cross that was awarded to Donald Watts. Mark Eslick’s status as KIA on October 12, 1944, is easy to find online but obviously at the time these events were happening Carl Solberg didn’t realize Eslick had been killed. And USS Cabot’s War History, Cabot’s Air Group 29 War History, and action reports from Air Group 29 all lack any mention of participation in searches. Solberg’s book is very good otherwise but on this particular point is has led historians astray.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m impressed. You know more about the battle than some of the authors I read. Weird but I did not get interested about WWII till I heard stories from my father on his last trip here in U.S. But then it was too late. I lost Dad in 2007, Mom passed on last year. I read as much as I can but there are so many books and too little time.

LikeLike